2. Lattice¶

A Lattice object describes the unit cell of a crystal lattice. This includes the

primitive vectors, positions of sublattice sites and hopping parameters which connect those sites.

All of this structural information is used to build up a larger system by translation.

Download this page as a Jupyter notebook

2.1. Square lattice¶

Starting from the basics, we’ll create a simple square lattice.

import pybinding as pb

d = 0.2 # [nm] unit cell length

t = 1 # [eV] hopping energy

# create a simple 2D lattice with vectors a1 and a2

lattice = pb.Lattice(a1=[d, 0], a2=[0, d])

lattice.add_sublattices(

('A', [0, 0]) # add an atom called 'A' at position [0, 0]

)

lattice.add_hoppings(

# (relative_index, from_sublattice, to_sublattice, energy)

([0, 1], 'A', 'A', t),

([1, 0], 'A', 'A', t)

)

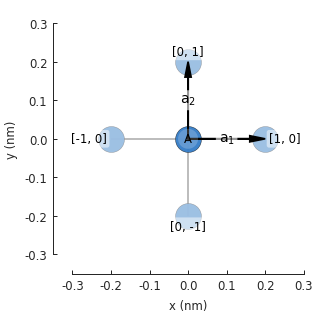

It may not be immediately obvious what this code does. Fortunately, Lattice objects

have a convenient Lattice.plot() method to easily visualize the constructed lattice.

lattice.plot() # plot the lattice that was just constructed

plt.show() # standard matplotlib show() function

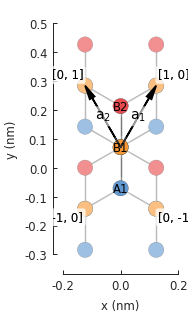

In the figure we see lattice vectors \(a_1\) and \(a_2\) which were used to initialize

Lattice. These vectors describe a Bravais lattice with an infinite set of positions,

where \(n_1\) and \(n_2\) are integers. The blue circle labeled A represents the atom

which was created with the Lattice.add_sublattices() method. The slightly faded out

circles represent translations of the lattice in the primitive vector directions, i.e. using

the integer index \([n_1, n_2]\).

The hoppings are specified using the Lattice.add_hoppings() method and each one consists

of (relative_index, from_sublattice, to_sublattice, energy):

- The main cell always has the index \([n_1, n_2]\) = [0, 0]. The

relative_indexrepresents the number of integer steps needed to reach another cell starting from the main one. Each cell is labeled with itsrelative_index, as seen in the figure. - A hopping is created between the main cell and a neighboring cell specified by

relative_index. Two hoppings are added in the definition: [0, 1] and [1, 0]. The opposite hoppings [0, -1] and [-1, 0] are added automatically to maintain hermiticity. - This lattice consists of only one sublattice so the

fromandtosublattice fields are trivial. Generally,from_sublatticeindicates the sublattice in the [0, 0] cell andto_sublatticein the neighboring cell. This will be explained further in the next example. - The last parameter is simply the value of the hopping energy.

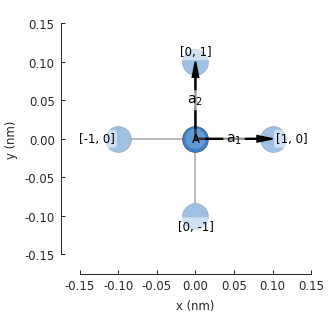

It’s good practice to build the lattice inside a function to make it easily reusable. Here we define the same lattice as before, but note that the unit cell length and hopping energy are function arguments, which makes the lattice easily configurable.

def square_lattice(d, t):

lat = pb.Lattice(a1=[d, 0], a2=[0, d])

lat.add_sublattices(('A', [0, 0]))

lat.add_hoppings(([0, 1], 'A', 'A', t),

([1, 0], 'A', 'A', t))

return lat

# we can quickly set a shorter unit length `d`

lattice = square_lattice(d=0.1, t=1)

lattice.plot()

plt.show()

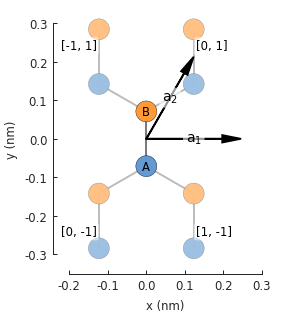

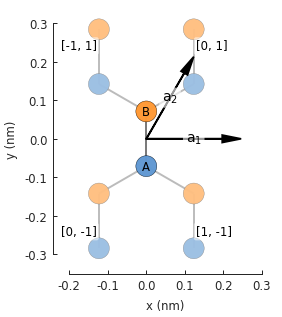

2.2. Graphene¶

The next example shows a slightly more complicated two-atom lattice of graphene.

from math import sqrt

def monolayer_graphene():

a = 0.24595 # [nm] unit cell length

a_cc = 0.142 # [nm] carbon-carbon distance

t = -2.8 # [eV] nearest neighbour hopping

lat = pb.Lattice(a1=[a, 0],

a2=[a/2, a/2 * sqrt(3)])

lat.add_sublattices(('A', [0, -a_cc/2]),

('B', [0, a_cc/2]))

lat.add_hoppings(

# inside the main cell

([0, 0], 'A', 'B', t),

# between neighboring cells

([1, -1], 'A', 'B', t),

([0, -1], 'A', 'B', t)

)

return lat

lattice = monolayer_graphene()

lattice.plot()

plt.show()

The Lattice.add_sublattices() method creates atoms A and B (blue and orange) at different

offsets: \([0, -a_{cc}/2]\) and \([0, a_{cc}/2]\). Once again, the translated cells are

given at positions \(\vec{R} = n_1 \vec{a}_1 + n_2 \vec{a}_2\), however, this time the lattice

vectors are not perpendicular which makes the integer indices \([n_1, n_2]\) slightly more

complicate (see the labels in the figure).

The hoppings are defined as follows:

([0, 0], 'A', 'B', t)specifies the hopping inside the main cell, from atom A to B. The main [0,0] cell is never labeled in the figure, but it is always the central cell where the lattice vectors originate.([1, -1], 'A', 'B', t)specifies the hopping between [0, 0] and [1, -1], from A to B. The opposite hopping is added automatically: [-1, 1], from B to A. In the tight-binding matrix representation, the opposite hopping is the Hermitian conjugate of the first one. The lattice specification always requires explicitly mentioning only one half of the hoppings while the other half is automatically added to guarantee hermiticity.([0, -1], 'A', 'B', t)is handled in the very same way.

The Lattice.plot() method will always faithfully draw any lattice that has been specified.

It serves as a handy visual inspection tool.

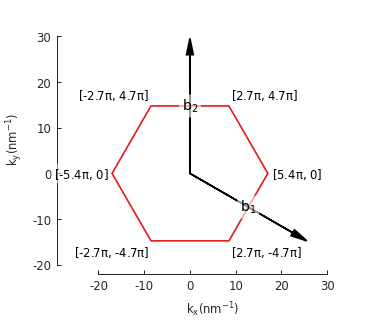

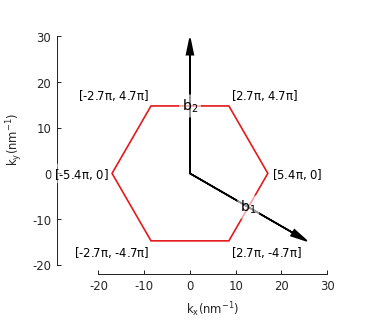

2.3. Brillouin zone¶

The method Lattice.plot_brillouin_zone() is another handy tool that does just as its

name implies.

lattice = monolayer_graphene()

lattice.plot_brillouin_zone()

The reciprocal lattice vectors \(b_1\) and \(b_2\) are calculated automatically based on the real space vectors. There is no need to specify them manually. The first Brillouin zone is determined as the Wigner–Seitz cell in reciprocal space. By default, the plot method labels the vertices of the Brillouin zone.

2.4. Material repository¶

A few common lattices are included in pybinding’s Material Repository. You can get started quickly by importing one of them. For example:

from pybinding.repository import graphene

lattice = graphene.bilayer()

lattice.plot()

2.5. Further reading¶

Additional features of the Lattice class are explained in the Advanced Topics

section. For more lattice specifications check out the examples section.

2.6. Example¶

This is a full example file which you can download and run with python3 lattice_example.py.

"""Create and plot a monolayer graphene lattice and it's Brillouin zone"""

import pybinding as pb

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

from math import sqrt

pb.pltutils.use_style()

def monolayer_graphene():

"""Return the lattice specification for monolayer graphene"""

a = 0.24595 # [nm] unit cell length

a_cc = 0.142 # [nm] carbon-carbon distance

t = -2.8 # [eV] nearest neighbour hopping

# create a lattice with 2 primitive vectors

lat = pb.Lattice(

a1=[a, 0],

a2=[a/2, a/2 * sqrt(3)]

)

lat.add_sublattices(

# name and position

('A', [0, -a_cc/2]),

('B', [0, a_cc/2])

)

lat.add_hoppings(

# inside the main cell

([0, 0], 'A', 'B', t),

# between neighboring cells

([1, -1], 'A', 'B', t),

([0, -1], 'A', 'B', t)

)

return lat

lattice = monolayer_graphene()

lattice.plot()

plt.show()

lattice.plot_brillouin_zone()

plt.show()